The Instagram account, “impact,” an account centered around spreading captivating news, recently posted about the amount of misinformation teens consume weekly. The post was informative and touched on a study by the News Literacy Project (NLP). In light of this post, this article will be a deep dive into misinformation, how it affects society, and what is being done to impede it.

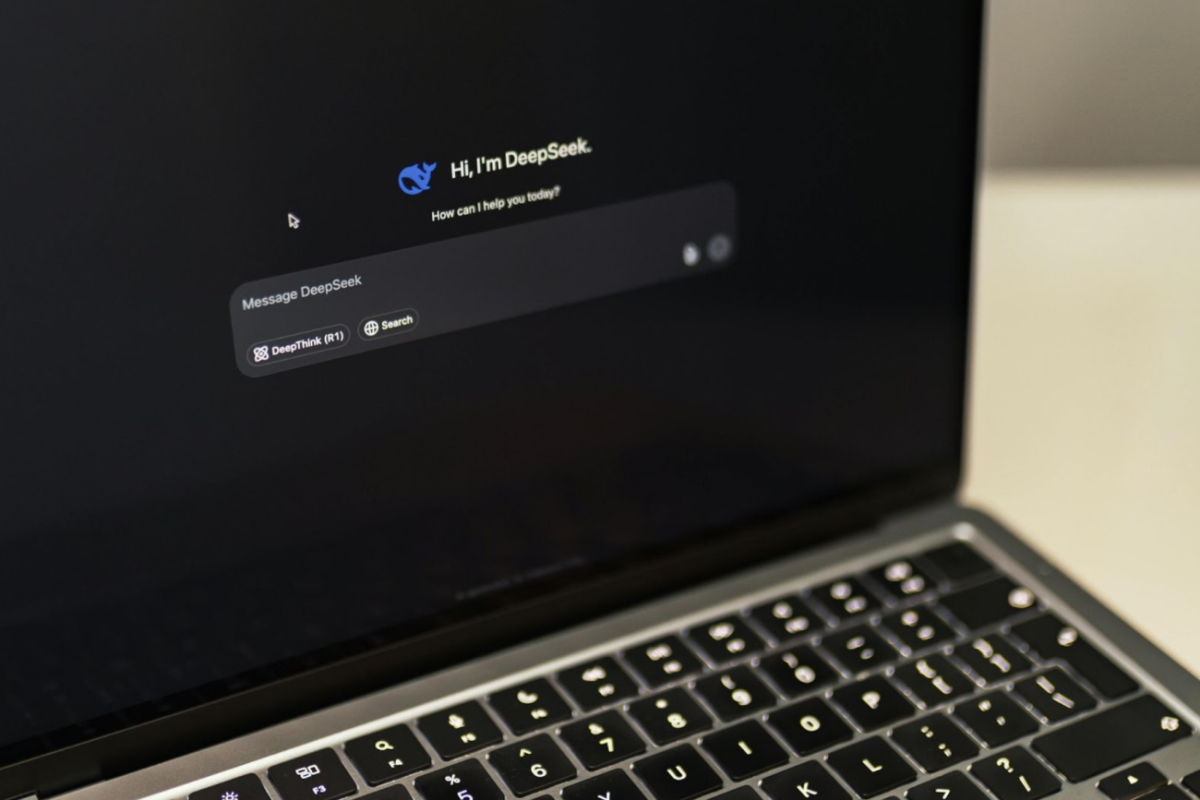

Misinformation is most prevalent on social media right now. Social media platforms do not have systems in place to check the accuracy of every single post. Viewers hope what they are reading is not misleading, selective, or false. Consider how 54 percent of U.S. adults use social media as their primary platform to stay informed on news. How much of their news is true?

When interviewing Matt Zwinge, a History and Government teacher, on the topic, he had a lot to say about how we, as a society, can improve on lessening the problem of misinformation. It would be extremely hard to change our society right now, but we should focus more on the younger generation, as they are next to vote and make those critical educated decisions.

His main point was regarding “willful ignorance” and how societally we have accepted not always having factual information. A prominent example he gave was Alex Jones, a radio host who convinced his followers that the Sandy Hook school shooting was faked, and that the parents of those children were crisis actors. His followers harassed the parents even though those events did occur, and their children died. Zwinge touches on the fact that because of willful ignorance, our society doesn’t take action until we see in big, bold red letters that the decision we made might not have been the best one. A prime representation is some of the top Google searches the day after the elections: “How to change my vote?” and “What is a tariff?”

When asked about how news literacy affects his teaching, Zwinge said, “I didn’t want to talk about the debate because of all the outrageous comments,” because much of what the candidates were saying was only to get votes, to get that extra supporter and not fact. For instance, Donald Trump’s idea to deport undocumented immigrants: this proposal gained a fair amount of supporters which in turn gave votes to Trump. However, those supporters did little research into what his plan would look like, such as how they would manage to sift through every single person, exemplifying the idea of willful ignorance. He commented that, in his Government classes, he now has to explain that when you have the chance to vote you need to make an informed decision by looking at multiple resources. Zwinge stated, “this also goes for my assignments. I encourage students to not use the first link that pops up, but to look at a few to make sure you are getting accurate information.”

The study from NLP showed precisely how informed teens are regarding news literacy. The report stated, “[only] half of teens can identify a branded content article as an advertisement, 52 percent can identify an article with ‘commentary’ in the headline as an opinion and 59 percent can recognize that Google search results under the label ‘sponsored’ indicate paid advertising. But less than two in 10 teens (18 percent) correctly answered all three questions asking them to distinguish between different types of information.” This demonstrates how harmful media can be, since anyone can post anything at any point in time, whether it be opinion or fact, and this is why media literacy is so important to be able to recognize.

NLP reported, “eight in 10 teens on social media say they see posts that spread or promote conspiracy theories.” They also noted that the top viewed conspiracies seen by teens on media were that the COVID-19 vaccine was dangerous, the Earth is flat, and that the 2020 elections were rigged.

Since false information is increasing, it is important to know what actions are being taken to solve the problem. NLP stated that in the U.S., “the bad news is that very few states require that news and media literacy be taught in school,” and that just 19 states have taken some legislative action. “Of those 19 states, as few as nine have included language in their media literacy legislation, including news literacy. As of now, just three of those nine states (Connecticut, Illinois, and New Jersey) explicitly require that news literacy instruction be included in at least some classrooms, and in one of those three states, Connecticut, the requirement goes into effect in 2025.” With these statistics, it is clear that the U.S. is not prepared for the growing dependency on social media.

In comparison, Finland is actively trying to improve their media literacy situation. They wrote out an educational plan to teach students in primary school how to question sources and spot misinformation. This model launched in 2014 due to increased disinformation spreading throughout Finland. They are now pushing past the school room and implementing programs in libraries to teach senior citizens media literacy skills. Impact says, “the country ranks first in all of Europe for resilience against misinformation,” showing other countries like the U.S. that it’s possible to help students spot false information online.